1 Introduction

Between 2010 and 2012, companies such as Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar were pivoting from their original business models (on-demand limousine service, closed-network ridesharing, and peer-to-peer carsharing respectively) towards a new type of service that would match any person looking for a ride to an informal network of non-professional drivers willing to provide one. Suddenly, anyone with a smartphone could access a whole new form of transportation – one that would cause headaches for transportation planners and policymakers for years to come.

The new service was reminiscent of many forms of informal transport from the past – e.g., jitneys, minibuses, and unregulated taxicab services from decades prior (and still present in some developing countries). However, the speed of development and expansion enabled by new technology and venture capital was unprecedented and ended up catching many regulators off guard. It wasn’t until late 2013 that California passed the first set of rules governing this kind of service, creating an entirely new regulatory category for the freshly coined “Transportation Network Companies” (TNCs).

Since then, there has been much scholarly research into the impacts of these companies as well as plenty of experimentation by cities around the world in applying policy to them. This paper reviews the most prominent academic literature and takes a snapshot of the regulatory environment in a few major cities to determine what best practices exist today. After building up an understanding of the positive/negative impacts of these operations and patterns in existing policy approaches, it’s determined that incremental regulation, targeted fees, and a holistic approach is necessary to effectively regulate this new transportation segment.

Due to the incipient nature of these services, note that terminology varies quite broadly across various sources. Academics tend to call these “ridesourcing” services (or “ridesplitting” for pooled rides) to distinguish them from traditional ridesharing (carpooling) and carsharing (short-term rentals), while governments often refer to them as TNCs (due to California’s influence), mobility service providers (MSPs), or private for-hire vehicles. The press tends to call them “ride-hailing” or “app-based rides”. These terms are all used interchangeably here, with a preference for “ridesourcing” or TNCs.

2 Literature Review

(Jin, et al. 2018) explores the impacts of ridesourcing services on the efficiency, equity, and sustainability of cities, presenting a systematic review of previous literature that is sometimes heavily debated. They generally conclude that ride sourcing has a positive impact on economic efficiency but note several negative effects when ridesourcing competes with public transit in high-density areas and when there is insufficient driver training or insurance. They remain inconclusive about ridesourcing’s impacts on traffic congestion and environmental impact.

(Tirachini and Río 2019) is an in-depth study of ridesourcing in Santiago de Chile, finding that its use primarily substitutes public transport and traditional taxis. They also find that the probability of a rider willing to share a trip decreases with income and that frequency of use overall is higher among more affluent and younger travelers. Notably, it doesn’t find a correlation between car availability and ridesourcing use, contrary to other studies.

(Rayle, et al. 2016) looks closer at ridesourcing in San Francisco, conducting intercept surveys from frequented hotspots in the city (North Beach, Marina, and North Beach). They find that users primarily cited ease of payment, short wait times, and fast trip times as reasons they used Uber/Lyft/Sidecar, though this varied slightly for those who used ridesourcing to replace a taxi trip versus a transit trip. Approximately half of ridesourcing trips replaced modes other than taxis (i.e., transit, walking, or biking).

(Zha, Yin and Yang 2016) conducts economic analyses of both a hypothetical monopolistic ridesourcing market and a duopoly situation, aiming to predict what would happen given manipulation of various regulatory variables. They conclude that the monopoly ridesourcing platform would maximize joint profits with drivers without regulatory intervention, but that this would not be sustainable and hence suggest regulation of at least two variables out of a set of three (trip fares, commissions paid to the platform, and number of total vehicles) to arrive at a second-best solution. In the case of a duopoly, they find that competition may not necessarily lower price levels or increase social welfare, so they recommend encouraging merger of the platforms and regulating them as a monopolist.

(Henao and Marshall 2017) discuss the need for a new kind of framework to investigate the impacts of ridesourcing – one that would consider the full scope of individual travel mode choices and impacts on the broader transportation system. They propose using door-to-door travel times (instead of just ride lengths), integrating spatially located sociodemographic data to evaluate transportation equity issues, and use of a bi-style modality classification (considering people who may act with different mode preferences in different situations), and building a statistical model of travel mode choice based on an econometric analysis of several factors (i.e., individual/household characteristics, modality style, modality resources, travel attributes, and land use characteristics).

(Mohamed, Rye and Fonzone 2019) evaluate the state of ridesourcing in London through interviews with policymakers, researchers, operators, and Uber drivers. They find that transport authorities lack the ability to monitor the use of services like Uber, making it difficult to assess their true impact and result in a dearth of knowledge among policymakers on how they should approach them. Generally, they want to be supportive of innovation but would only want to encourage ridesourcing services where they truly complement public transport and reduce single car occupancy and car ownership.

(Vignon, Yin and Ke 2021) expands on the economic modeling work of previous research to determine the best ways for regulators to induce efficient outcomes for monopolistic ridesourcing platforms. They include the presence of congestion as an externality and integrate both solo and pooling services. They conclude that coupling a single commission cap and a congestion toll (scaling with the amount of congestion) can result in a sustainable equilibrium.

(Agarwal, Mani and Telang 2019) study the impact of ridesourcing services on traffic congestion in three Indian cities by looking at what happens when the services become unavailable. They see that periods of ridesourcing unavailability result in up to 14.8% reduction in travel times, providing evidence that there is a negative externality for policymakers to consider. They also provide evidence for reasons behind the congestion, including deadheading and substitution of public transit.

(Erhardt, et al. 2019) set out to determine the effect of ridesourcing on congestion in San Francisco by scraping data from the APIs of the two largest TNCs, processing this to associate TNC activity with specific road segments and controlling for other congestion factors using the SF-CHAMP travel demand model. They conclude that TNCs were the biggest factor in the growth of traffic congestion and deterioration of travel time reliability between 2010 and 2016.

(Aarhaug and Olsen 2018) discuss how the needs for regulation in unscheduled passenger transport are evolving due to the rise in ridesourcing services. They evaluate three potential scenarios and conclude that the parameters for regulation will shift towards congestion, competition, and labor issues.

(Napalang and Regidor 2017) assess the effectiveness of regulation of ridesourcing services in Metro Manila. They find that regulations exist for basic licensing and operations but have been limited in terms of rider reliability (passengers being declined service), safety (lack of insurance for passengers), and affordability (surge pricing). They recommend further evaluation on the effects on the sustainability of transportation (i.e., mode shifts).

(Luo 2019) explores ways of implementing congestion pricing specifically on ridesourcing services. A novel simulation approach is developed that can compute an optimal congestion price based on a metamodel representation of traffic flow.

3 Findings

3.1 Ridesourcing Impacts

Over the last decade as ridesourcing services have become more established around the world, it’s clear that they present a complex mix of both positive and negative impacts on cities. Understanding the full breadth of these impacts will be crucial for policymakers as they attempt to make informed decisions about regulation. Ideally, cities will find ways to leverage the strengths and benefits of ridesourcing while mitigating its most harmful consequences.

3.1.1 Positive Impacts

Ridesourcing services have notable benefits when compared against traditional, regulated taxi services. (Rayle, et al. 2016) They often provide shorter and more reliable wait times than taxis, reach poor neighborhoods with insufficient taxi services, and are better at matching supply and demand for trips. Mutual trust systems (i.e., ratings) also lead to better perceived safety for both drivers and passengers.

It is also possible for ridesourcing to complement or improve upon public transit service in certain conditions. For example, in low-density areas, ridesourcing can be more efficient than dedicated transit routes. Ridesourcing can also act as first/last mile feeders to public transit. On nights and weekends when transit service may not be available or frequent enough, ridesourcing can act as a valuable, complementary option.

3.1.2 Negative Impacts

3.1.2.1 Traffic Congestion

A continuous stream of studies has repeatedly shown that ridesourcing contributes to traffic congestion. One recent study demonstrated that TNCs led to increased road congestion in the United States both in terms of intensity (by 0.9%) and duration (by 4.5%). (Diao, Kong and Zhao 2021) The mere availability of ridesourcing may actually result in more trips being taken, causing an induced travel effect of ~8%. (Henao and Marshall 2017)

Congestion impacts are much greater in urban cores. For example, in a Fehr & Peers study commissioned by Uber & Lyft, as much as 12.2-13.4% of VMT in San Francisco County was generated by TNCs in August 2018 (McGuigan and Pangilinan 2019).

SFCTA confirmed this with their own study, finding that TNCs accounted for ~50% of the change in congestion (measured in vehicle hours of delay, vehicle miles travelled, and average speeds) in San Francisco between 2010 and 2016. They also found that the effects were concentrated in the densest parts of the city, contributing to almost 75% of increased delay in District 3 (which includes the Financial District). (San Francisco County Transportation Authority 2018, Erhardt, et al. 2019)

VMT increases persist even when pooling is considered. This is because pooled options mainly draw riders from public transit/biking/walking, and additional dead-head miles are added before each pickup. A study found that these combined effects led to at least a doubling of VMT impact when comparing ridesourcing trips with riders’ previous mode. (Schaller, Can sharing a ride make for less traffic? Evidence from Uber and Lyft and implications for cities 2021)

3.1.2.2 Competition with Sustainable Modes

In high-density areas, ridesourcing often competes with (more than complements) public transit and other more sustainable mode choices. It has been shown that ridesourcing passengers decrease their use of public transit by 6% on average. 49-61% of ridesourcing trips would not have been made or would have occurred via walking, biking, or transit. (Clewlow and Mishra 2017) In Santiago de Chile, for every rider that combined a ridesourcing trip with public transit, another 11 riders replace transit trips altogether. (Tirachini and Río 2019)

While Uber and Lyft are increasingly looking to partner with transit agencies for last mile service in suburban environments (Woodman 2016), such arrangements have been found to be unsustainable – particularly if government subsidization is required. (Cecco 2019)

3.1.2.3 Car Ownership

Ridesourcing companies often make the claim that their services can encourage less car dependency and thus lead to fewer people purchasing or holding on to their own cars. However, it’s been shown that TNC entry into urban areas actually causes vehicle ownership to increase by 0.7% on average. This effect seems to be even larger in car-dependent and slow-growth cities. (Ward, et al. 2021)

3.1.2.4 Pollution

Mostly due to the increases in VMT produced, ridesourcing trips today result in ~69% more climate pollution on average than the trips they replace. (Anair, et al. 2020)

3.1.2.5 Equity Impacts

There are several ways that ridesourcing can magnify inequities already present in marginalized communities. One fundamental way is due to their nature as smartphone-driven experiences. The digital divide that persists across the globe means that anyone without a relatively modern smartphone will not be able to participate either as a rider or a driver. In places where there is little investment in transportation alternatives to ridesourcing, these already disadvantaged individuals may just end up perpetually stranded.

Even for those able to obtain a smartphone, use of ridesourcing services can quickly become exploitative. Riders with few options can face high costs for rides (and prices can “surge” often with no caps). Drivers who enter the sharing economy as “contractors” are often misled about potential earnings and fall prey to high commissions and vehicle maintenance costs not covered by platform owners. Insufficient driver training and insurance can also lead to financial ruin when accidents occur. (Jin, et al. 2018)

3.2 Existing Regulation

Cities around the world have reacted to ridesourcing services with a wide and ever-evolving array of attempts at regulation. Here are a few policy snapshots from several notable cities.

3.2.1 San Francisco

Although the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) has jurisdiction over taxis in the city, it has minimal regulatory authority over ridesourcing services due to a series of historical events during the mayorship of Ed Lee. (Flores and Rayle 2017) Instead, as part of a coordinated effort to support “sharing economy” companies during the economic recovery of 2011-2012, the business-friendly California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) became the primary regulatory body and quickly created a new loosely-regulated category for “Transportation Network Companies” (TNCs), thus coining the term and initial policies that would subsequently be copied by many other cities.

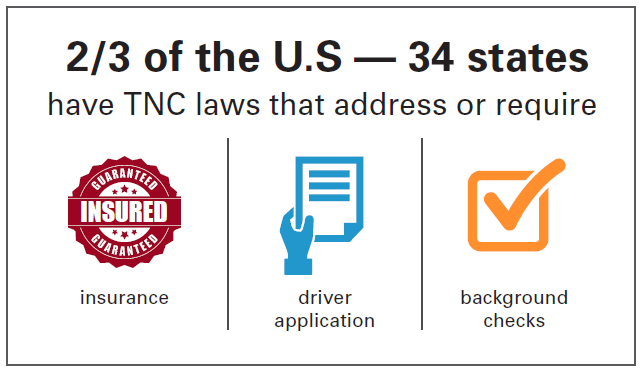

The CPUC requires TNC drivers to undergo national criminal background checks, a 19-point vehicle inspection annually or every 50,000 miles, and roadway safety training. DMV rules also prohibit them from driving more than 10 consecutive hours, resetting after an 8-hour rest period. TNC companies must provide $1M commercial insurance, allow passengers to request a wheelchair-accessible vehicle, and cannot operate their own fleet (but can rent vehicles to TNC drivers). Annual data reporting requirements include the provision of accessible vehicles, services provided by zip code, problems reported, hours/miles logged by drivers, and drivers completing training – though this data is not readily accessible by the public or other governmental agencies. 0.33% of gross California revenues are paid into a CPUC Transportation Reimbursement Account for administration, and recently a $0.10 “Access for All Fee” per trip has been added to support the expansion of wheelchair accessible vehicles (WAV). These basic operational requirements are similar across many states. (Moran, et al. 2017, San Francisco County Transportation Authority 2017)

The issue of whether TNC drivers should be considered independent contractors or full employees has been under contention in recent years. As of 2020, California Assembly Bill (AB) 5 established a test that would define TNC drivers as employees with legally required benefits (e.g., healthcare, unemployment, etc.). However, Proposition 22 specifically carved out an exemption for “app-based” drivers and guaranteed certain benefits in place of what state labor laws would have provided, though it’s claimed that the value of these benefits would be substantially less. (Sammon 2020) As the repercussions of Proposition 22 ripple through California and similar legislation is drafted in other states, the current federal administration is likely to weigh in on this question as well.

3.2.2 New York City

Unlike in San Francisco, TNCs in New York City are not regulated by the state. Instead, the local Taxi & Limousine Commission directly licenses and regulates “for-hire vehicles”, requiring drivers to undergo background checks, annual drug testing, and defensive driving courses every three years. Vehicles are to be inspected every 4 months, and an accessible vehicle must be arranged upon request.

In 2018, New York City became the first major U.S. city to directly limit ridesourcing services by implementing a cap on new for-hire licenses in an attempt to ease traffic congestion, stem the flood of new drivers making the profession unsustainable, and give the city time to study ridesourcing effects as well as set a minimum pay rate for drivers. This pause on licenses was made permanent the following year, though there was a notable exception for electric vehicles. (Revel, a newcomer to the scene, is attempting to use the exception as a loophole to bring in their own for-hire drivers.)

3.2.3 London

Transport for London (TfL) regulates ridesourcing services under the same rules as all other private hire vehicles (PHV). Operators are required to keep records of driver’s licenses, insurance, vehicle details, bookings, passenger information, and fares. TfL’s interest is mostly focused on ensuring safety, famously denying the renewal of Uber’s license to operate in 2017 due to concerns about criminal offenses and lax background checks. While London’s city center has a congestion pricing scheme in place, all PHVs (including ridesourcing services) currently have an exemption – though authorities are considering removing this.

In 2018, the Mayor’s Transport Strategy directed the investigation into new policies to increase accessibility (setting a minimum percentage of wheelchair-accessible vehicles), mandate data sharing, improve driver conditions (allowing reasonable working hours and breaks), and enhance user awareness of driver licensing and feedback mechanisms. (Transport for London 2018)

3.2.4 São Paulo

Both drivers and platform operators are required to obtain permits from a municipal agency before offering service. Requirements include maintaining records for each driver, using digital maps, communicating fares / enabling electronic payments, capping fares to a maximum set by the Municipal Road Use Committee, enabling users to publicly evaluate quality, and providing electronic receipts. São Paulo has also notably implemented a road use charge per kilometer traveled (including dead-heading), which can incentivize shorter trips. (Yanocha and Mason 2019) There is also an equity component built in, requiring TNCs allot a percentage of VKT credits consumed per month for use by female drivers.

In addition to requiring TNCs to share data to track the consumption of road use credits, the city has also asked for data on trip origins/destinations, length/distances, wait times, route maps, prices, driver IDs, and user evaluations.

3.2.5 Beijing (China)

Didi Chuxing, the dominant ridesourcing platform in China, was operating in a legal grey zone until 2016 when China approved a new regulatory framework. At that point, drivers were required to have three years’ experience, have no criminal record, and be licensed by local taxi regulators. Vehicles needed to have odometer readings of less than 600,000 kilometers. (Mozur 2016)

Since then, government officials have been gradually ratcheting up the regulations in response to safety incidents, culminating in a 2020 requirement to have “double licenses” (one for the driver and a commercial license for the vehicle) that has made it financially infeasible for any would-be casual driver to participate. Local authorities have been suspending the service sporadically as they find violations in their regions.

At this point, Didi is investing in autonomous vehicles, recently rolling out a test fleet in Shanghai. It is also taking a global lead role in working with regulators to draft new rules for this ridesourcing segment. (Shicong 2020)

4 Synthesis

Broadly speaking, possible efforts to regulate ridesourcing services span five major categories – reflecting the negative impacts that governments or regulators may wish to avoid, or values they may wish to promote: safety, taxes (pricing fairness), transparency, access/equity, and sustainability.

4.1 Safety

It’s clear that regulators’ initial top priority when considering ridesourcing services is safety – both for drivers and for passengers. This explains why every jurisdiction starts with a minimum bar for driver qualifications, such as requiring licensing, training, testing, background checks, or minimum years of experience. Efforts to limit the length of driving time per day also demonstrate the interest in making sure drivers are always alert and capable of the job.

Most will go on to verify vehicle safety as well, mandating inspections and enforcing a maximum age or mileage. Vehicle inspections are typically required before starting service and regularly (based on time or mileage) after that.

Finally, insurance requirements are added on top to ensure liabilities can be accounted for. These can be in the form of insurance carried by the driver, commercial insurance carried by the platform company, or both.

4.2 Taxes & Pricing

Given the number of documented negative externalities that come with ridesourcing services, it is no wonder that regulators are eager to assess taxes and fees on both platform companies and trips themselves.

States typically begin by charging an annual permit (or business license) fee to each TNC company, ranging from hundreds of dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is usually combined with a per-trip fee (flat or percentage) so revenues can scale with the growth of the ridesourcing service. Some states go further and charge a tax on total gross income, which can prove very lucrative in major markets with a lot of ridesourcing activity.

On the flip side, if governments wish to encourage use of ridesourcing to replace other unsustainable modes of transportation, they may actually choose to implement policy to make rides cheaper for passengers. This can be done by either capping fares (i.e., limiting “surge” pricing) or directly subsidizing rides as part of a holistic local transportation plan.

4.3 Transparency

One of the most common frustrations expressed by policymakers is how ridesourcing operations are opaque by default. TNCs are typically reluctant to share data about how their services are being used because it may hurt their ability to compete in the market, but policymakers cannot make truly informed decisions without at least some elements of this data. Customer privacy is also cited as a concern, but there are ways to aggregate and anonymize data to address this.

Hence, data sharing is becoming more and more common of a regulatory requirement, with jurisdictions getting increasingly emboldened to ask for more detailed information including locations of pick-ups and drop-offs, routes, dwell times, miles logged by drivers (including deadheading), ratings, and more.

Some key principles for data sharing include: (Fagan, Comeaux and Gillies 2021)

- Transparency to the public in why data is being collected

- Responsible stewardship of data (keeping confidential information safe)

- Promoting equity, targeting economic/social disparities, and encouraging affordability

- Ensuring data and its insights provide real utility to the public

- Preventing data silos and promoting data portability

4.4 Access & Equity

Ensuring access to ridesourcing services for those with disabilities is already a common requirement. This is typically done with a mandate on a percentage of wheelchair-accessible vehicles, or a guarantee that such a vehicle is always available upon request.

A long-standing regulation on taxi services usually states that service cannot be denied to anyone based on whether they are a member of a protected class, but this is often violated in practice. For those jurisdictions that regulate TNCs the same as taxis, such rules still apply.

Some forward-thinking jurisdictions have attempted to tackle the challenge of driver exploitation (by classifying drivers as full employees as opposed to independent contractors), but these efforts have been met with strong political pushback from ridesourcing companies. The fight over how to classify drivers in a way that ensures they can earn a living wage and proper benefits will continue for the foreseeable future.

4.5 Sustainability

The next frontier in ridesourcing regulation is clearly in how to address their negative impacts on traffic congestion and environmental impact (i.e., through carbon emissions). Capping the number of drivers/vehicles is a good start, but the history of the taxi industry shows us that this solution may have unintended consequences in the long-term.

Instead, the best solutions seem to come in the form of incentives for shared, shorter, and less frequent trips. Road use charges (i.e., a vehicle-miles travelled tax or congestion pricing) discourage drivers and riders from making wasteful or inefficient trips and minimize dead-heading in dense urban areas.

Jurisdictions have also been creative in designing effective incentives to use greener vehicles for ridesourcing, granting fee exemptions or waiving caps on new licenses for zero-emission vehicles.

5 Recommendations & Conclusion

Given the historical tendency of ridesourcing companies to “ask for forgiveness, not for permission” when entering new markets, it is no wonder that it has been challenging for policymakers to keep up. To this day, more than a decade after the first ridesourcing services emerged, there is still no widely accepted best practice for how to effectively regulate them.

However, based on the many academic papers on the subject thus far and the just-in-time experimentation actively being conducted in cities across the globe, here are a few concrete ideas that may help guide regulators on their journey towards building a better relationship with ridesourcing in their cities.

5.1 Incremental Regulation

Ridesourcing companies have always been a moving target, and there are no signs they will stop evolving anytime soon. Their business models are not always financially sustainable, so we can expect that they will continually attempt to introduce new services and modify how their platforms work. For example, some are already trying to integrate bikeshare or public transit services into their user interfaces – whether this is just a temporary bid to placate ailing transit agencies or a genuine attempt at fostering a multi-modal lifestyle for their users remains to be seen.

In any case, regulators can start with the fundamentals and build on top of them. For example, it’s already well established that safety is a value that cannot be compromised, so rules around driver qualifications and vehicle safety should be implemented first. After a basic safe service is established, policies around data sharing and initial taxes/fees should be implemented. Regulations around sustainability and access/equity should only be attempted once proper administrative funding and usage data is collected.

The reasoning for this sequence is twofold. First, regulations around sustainability and access are only going to be effective if there is sufficient study and understanding of the ridesourcing operations, so it would be premature to propose blanket rules before data and research funding is available. Second, a healthy relationship between regulators and companies hinges on trust and collaboration – which will be much easier to establish if the regulators show good faith and reasonable order-of-operations (process). This incremental approach also enables ample opportunity for communication between ridesourcing companies and the regulators, to ensure that policies being developed won’t be outdated or irrelevant the moment they are released.

5.2 Targeted Fees

When it comes to taxing the externalities of ridesourcing, academic research can help establish a starting point for what is likely going to be a lifetime of negotiations between ridesourcing companies and regulators. However, it’s important for the regulator to first consider what goals are most important in their jurisdiction. In a low-density suburb where officials might want to encourage the use of ridesourcing over private, single-occupancy vehicles, taxation efforts might be better aimed at car ownership in general as opposed to ridesourcing trips.

In high-density, urban cores where ridesourcing is known to cause unwanted traffic congestion, best practices for taxation may be more straightforward. For example, in New York City, a report estimated that a mandate to limit unoccupied time (when driving between trips) combined with congestion pricing and a per-trip fee on trips beginning in Manhattan would be effective enough to reduce the number of vehicles in the CBD by 20% or more, reversing most of the congestion seen since 2010. (Schaller, Empty Seats, Full Streets 2017) More generally, a cap on commissions (for the ridesourcing platform) combined with a congestion toll (however small) can induce any desired, sustainable equilibrium. (Vignon, Yin and Ke 2021)

We also know that road use charges (fee per mile or kilometer travelled) are more effective than a simple percent surcharge, which in turn is more effect than a flat per trip surcharge alone. We also know that congestion pricing is very effective at reducing VMT, but it needs to apply to all vehicles (not just TNCs or non-TNCs) to really shift mode choices away from automobiles entirely. (Yanocha and Mason 2019)

5.3 Holistic Approach

Finally, it’s important to take a step back and remember the bigger picture. When all is said and done, real people will demand safe, reliable, and affordable transportation options to go about their business. They will travel using the option that is most convenient for them depending on their context and their ability to pay. It is up to planners and policymakers to set up the right infrastructure and incentives that will guide people towards sustainable choices, regardless of what they might be at any given moment. Ridesourcing will be a part of this picture for the foreseeable future, and regulations on it cannot ignore the broader context.

This means that there will be times and places where ridesourcing will be the “right” choice, and then it should be fully supported. For example, ridesourcing should be available and reasonably affordable when public transit isn’t running or in low-density areas with no alternative coverage. Alternatively, ridesourcing can serve as the first/last mile connection that enables someone to use public transit for the bulk of their journey.

The nascent concept of “mobility-as-a-service” (MaaS) embodies this idea and is an area ripe for further research. Ridesourcing companies are in a prime position to expand into offering a veritable feast of transport options that one can mix-and-match as needed, and policymakers should be cognizant of the implications. Perhaps future ridesourcing regulations will need to be developed around time of operations or geographical limits so as to ensure an optimal balance of mode use across an average person’s daily trips. As this concept develops further, it will be even more essential for planners to maintain clear regional mobility goals and coordination between existing services.

6 Bibliography

- Aarhaug, Jørgen, and Silvia Olsen. “Implications of ride-sourcing and self-driving vehicles on the need for regulation in unscheduled passenger transport.” Research in Transportation Economics 69, 2018: 573-582.

- Agarwal, Saharsh, Deepa Mani, and Rahul Telang. The Impact of Ride-hailing Services on Congestion: Evidence from Indian Cities. Hyderabad: Indian School of Business, 2019.

- Anair, Don, Jeremy Martin, Maria Cecilia Pinto de Moura, and Joshua Goldman. “Ride-Hailing’s Climate Risks: Steering a Growing Industry toward a Clean Transportation Future.” Union of Concerned Scientists. February 25, 2020. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/ride-hailing-climate-risks (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Cecco, Leyland. The Innisfil experiment: the town that replaced public transit with Uber. July 16, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jul/16/the-innisfil-experiment-the-town-that-replaced-public-transit-with-uber (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Clewlow, Regina R., and Gouri Shankar Mishra. Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States. Research Report, Davis, CA: UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies, 2017.

- Diao, Mi, Hui Kong, and Jinhua Zhao. “Impacts of transportation network companies on urban mobility.” Nature Sustainability, 2021.

- Erhardt, Gregory D., Sneha Roy, Drew Cooper, Bhargava Sana, Mei Chen, and Joe Castiglione. Do transportation network companies decrease or increase congestion? Research Article, San Francisco, CA: Science Advances, 2019.

- Fagan, Mark, Daniel Comeaux, and Benjamin Gillies. Autonomous Vehicles Are Coming: Five Policy Actions Cities Can Take Now to Be Ready. Cambridge, MA: Taubman Center for State and Local Government, 2021.

- Flores, Onesimo, and Lisa Rayle. “How cities use regulation for innovation: the case of Uber, Lyft and Sidecar in San Francisco.” World Conference on Transport Research. Shanghai: Transportation Research Procedia 25, 2017. 3756-3768.

- Henao, Alejandro, and Wesley Marshall. “A Framework for Understanding the Impacts of Ridesourcing on Transportation.” In Disrupting Mobility, by Cham Springer, 197-209. 2017.

- Jin, Scarlett T., Hui Kong, Rachel Wu, and Daniel Z. Sui. “Ridesourcing, the sharing economy, and the future of cities.” Cities 76, 2018: 96-104.

- Lavieri, Patrícia S., Felipe F. Dias, Natalia Ruiz Juri, James Kuhr, and Chandra R. Bhat. “A Model of Ridesourcing Demand Generation and Distribution.” Transportation Research Record, 2018: 31-40.

- Luo, Qi. “Dynamic Congestion Pricing for Ridesourcing Traffic: a Simulation Optimization Approach.” 2019 Winter Simulation Conference. IEEE, 2019. 2868-2869.

- McGuigan, B., and C. Pangilinan. Estimated TNC Share of VMT in Six US Metropolitan Regions. Memorandum, San Francisco, CA: Fehr & Peers, 2019.

- Mohamed, Mohamed Jama, Tom Rye, and Achille Fonzone. “Operational and policy implications of ridesourcing services: A case of Uber in London, UK.” Case Studies on Transport Policy, 2019: 823-836.

- Moran, Maarit, Ben Ettelman, Gretchen Stoeltje, Todd Hansen, and Ashesh Pant. Policy Implications of Transportation Network Companies. Austin, TX: Texas A&M Transportation Institute, 2017.

- Mozur, Paul. Didi Chuxing and Uber, Popular in China, Are Now Legal, Too. July 28, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/29/business/international/china-uber-didi-chuxing.html (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Napalang, Ma. Sheilah G., and Jose Regin F. Regidor. “Innovation Versus Regulation: An Assessment of the Metro Manila Experience in Emerging Ridesourcing Transport Services.” Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, 2017: 343-355.

- Paredes, Luis Lozano. Decent Work for Ride Hailing Workers in the Platform Economy in Cali, Colombia. CIPPEC, 2020.

- Rayle, Lisa, Danielle Dai, Nelson Chan, Robert Cervero, and Susan Shaheen. “Just a better taxi? A survey-based comparison of taxis, transit, and ridesourcing services in San Francisco.” Transport Policy 45, 2016: 168-178.

- Sammon, Alexander. How Uber and Lyft Are Buying Labor Laws. October 5, 2020. https://prospect.org/api/amp/labor/how-uber-and-lyft-are-buying-labor-laws/ (accessed May 9, 2021).

- San Francisco County Transportation Authority. “The TNC Regulatory Landscape.” SFCTA. December 2017. https://www.sfcta.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/TNC_regulatory_FINAL.pdf (accessed May 9, 2021).

- San Francisco County Transportation Authority. TNCs & Congestion. Draft Report, San Francisco, CA: SFCTA, 2018.

- Schaller, Bruce. “Can sharing a ride make for less traffic? Evidence from Uber and Lyft and implications for cities.” Transport Policy 102, 2021: 1-10.

- Schaller, Bruce. Empty Seats, Full Streets. Commissioned Report, Brooklyn, NY: Schaller Consulting, 2017.

- Shicong, Dou. China’s Didi Chuxing Helps Draft World’s First Set of Rules for Robotaxis. August 6, 2020. https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/china-didi-chuxing-helps-draft-world-first-set-of-rules-for-robotaxis (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Tirachini, Alejandro, and Mariana del Río. “Ride-hailing in Santiago de Chile: Users’ characterisation and effects on travel behaviour.” Transport Policy 82, 2019: 46-57.

- Transport for London. “Policy statement: Private hire services in London.” London Taxi and Private Hire. February 1, 2018. http://content.tfl.gov.uk/private-hire-policy-statement.pdf (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Vignon, Daniel A., Yafeng Yin, and Jintao Ke. “Regulating ridesourcing services with product differentiation and congestion externality.” Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2021: 103088.

- Wang, Hai, and Hai Yang. “Ridesourcing systems: A framework and review.” Transportation Research Part B 129, 2019: 122-155.

- Ward, Jacob W., et al. “The impact of Uber and Lyft on vehicle ownership, fuel economy, and transit across U.S. cities.” iScience, January 2021: 101933.

- Woodman, Spencer. Welcome to Uberville. September 1, 2016. https://www.theverge.com/2016/9/1/12735666/uber-altamonte-springs-fl-public-transportation-taxi-system (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Yanocha, Dana, and Jacob Mason. “Ride Fair: A Policy Framework for Managing Transportation Network Companies.” Institute for Transportation & Development Policy. March 13, 2019. https://www.itdp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019.03.13.TNC-Policy.V9.pdf (accessed May 9, 2021).

- Zha, Liteng, Yafeng Yin, and Hai Yang. “Economic analysis of ride-sourcing markets.” Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2016: 249-266.

Another great reference explaining all the ways TNCs are bad for sustainable transportation: https://usa.streetsblog.org/2019/02/04/all-the-bad-things-about-uber-and-lyft-in-one-simple-list/

LikeLike